Betty started work at Royal Crown Derby as an apprentice gilder on June 4th 1934. In her excellent book “Gold in my Veins” Betty records her experience of working at the factory. At this time an Apprenticeship lasted for a period of 5 years. Previously the parents of an Apprentice had been required to pay for the Apprenticeship, but by this time the company met the cost, retaining a small percentage of the Apprentice’s total earnings by way of payment until the end of the 5 year term. The working day began at 8.00 a.m. She would collect a brass token from the Lodge and place it in a slot in the wall to record her attendance. She was taken to the apprentice gilding room to meet Miss Meakin, the head of the training department. She describes the training room as “Rectangular with six tall windows on one side and opposite were deep shelves of pens as they were known used for storage. Below each window was a long, scrubbed wooden table with three-legged wooden stools either side”. A typical class at this time consisted of twelve girls, two beginners and the rest older and at different stages of development.

She was given a white cup marked “workman’s use” and fitted for the correct height stool “as it was most important that we sat comfortably with the elbows just resting on the table.” Part of her training involved the use of the banding wheel, a very difficult skill to master. Apprentices were taught to mix colour – “best red” being used instead of gold during the training process. This had an iron ore component and was about the same weight in the brush as gold.

Betty “was given a 5 inch square tile with a large blob of “best red” in the middle. This colour had been ground and mixed by another fourteen year old whom I met for the first time that fateful Monday morning and who became a lifelong friend. The weekly grinding of colour became all part of our apprenticeship and what a mess we made of it sometimes!”

She was given a squirrel hair brush about three quarters of an inch long with a very fine point. She explains that learning to control the brush was of utmost importance and “took quite a while”. The brush needed to be long to hold enough colour (later gold) to both maintain the intensity and complete the intricate strokes.

Miss Meakin gave Betty a white five inch plate, put the “brush into the colour and conditioned it, gently working it to a point. Sometimes these points were too long and needed trimming. A very steady hand and good sharp scissors were needed for this and it wasn’t something that I attempted for many years, especially as we had to buy our own brushes once we had reached piecework status. I had many strokes to practise and brushes to wear out before I became proficient.”

Miss Meakin “then painted a series of strokes about half an inch in length and quite close together all exactly the same length leaving a gap; she did a further set but graduating each stroke until the final one was half the length of the first one, she put a ring of small dots at the base of the shortest one and then it was my turn. My instructions were to fill up the plate trying to copy the set pattern and make the strokes as demonstrated. It may sound simple but on proffering the plate for inspection I was told to clean it off and do it again. I was to hear that phrase many many times during the next couple of years”

As she gradually controlled the long brush more intricate patterns were introduced together with the different shape plates and an extensive range of hollow ware items.

Chores included sweeping the stairs and cleaning the room. Two girls took it in turn each week to collect hot water in buckets from the plate makers' department. This had to be carried up two flights of stairs. White cotton waste collected from the maintenance department was washed and dried and then used for removing gold strokes which were not up to standard as well as cleaning gold from the gilders' fingers and all equipment and tables. This precious waste was then collected in the gold grinding room and sent off to the smelting company for recycling.

Betty worked a 54 hour week, 8.00 a.m. – 5.45 p.m. each day with an hour and a half lunch break. On Saturdays she worked 8.00 a.m. – 12 noon. Miss Meakin was prepared to leave the girls to their own devices from time to time, which resulted in some lighter moments amongst the gilders. She was considerate enough to make sufficient noise outside the room on her return to give them time to assume a focused composure!

The senior girls' finished work “was stored on the shelves or 'pens' as they were known until a firing day was approaching when it was carried out, something we were asked to help with and which was a little bit scary until we were used to it. The apprentice room was up two flights of steps, eight and twelve respectively with a metal handrail for safety. Flat-ware, plates and saucers of all sizes were fired on cranks, unusual three-legged stands made of stoneware covered in a thick treacly glaze which would not melt at the 780 degrees necessary to fire the gold and enamel. Each crank was hollowed to take the saucer or plate and the top of each crank leg was indented in order to stack them one upon the other. We carried them out six at a time, quite a weight if they were 10 inch plates and of course two hands were needed. Hollow ware was carried in wooden boxes. All the girls' work was checked and inspected by Miss Meakin and was taken straight to the kiln for firing.”

“Work from the Women gilders was taken to the same kiln but was placed into a room we called the 'receive' where it was checked for quality and for any marks which would then be cleaned off. Gilding being the final decorating process it was so easy to leave a tiny mark on the back of the plate or inside a cup which if it was fired on would need polishing off, a costly operation using a lathe which of course added to the eventual price”.

Another task was the collection of the “Mikado” ware for finishing. She describes it as follows:- “We crossed the cobbled yard in a slightly different direction and mounted what was almost a spiral staircase with an iron handrail to the Glost Warehouse, here was stored all the white ware and under glaze blue of all designs. Mikado was an all over pattern under the glaze which just needed the gold to finish it off. We applied it to the handles, footlines and edges, we sometimes collected twenty dozen pieces at a time, hollowware in boxes and flatware carried in piles of three to four dozen in each pile or 'bung' dependent on size. The idea being that you held your left hand under the bottom one and gently rested the 'bung' of plates or saucers up the arm. It was quite comfortable, but felt very heavy by the time we arrived back in our room. I well remember the occasion when I missed my footing while carrying a 'bung' of five inch plates and ended in a heap at the foot of the stairs. The warehouse manager’s head appeared over the banister as he yelled “how many have you broken?” – and he didn’t mean bones! – fortunately no real harm was done to me, lots of bruises and a scraped elbow was about the sum total.”

She describes the use of the banding wheel as follows: “The floor standing wheel was positioned to the left in order that the right arm could rest on the table as we turned towards the wheel holding the liner, a long wedge shaped brush, but before we actually got to using the liner we had to master the art of centring the plate, which means placing the plate on the wheel and turning it fairly quickly, gently tapping the edge until the plate appears to be standing still which means that it is exactly in the middle of the spinning wheel. We were learning to paint fine lines, sometimes two placed closely together, so it was therefore essential that the plate was centred correctly. It was also very easy to send the plate flying off that same spinning wheel – one or two ended up on the floor. The secret of lining and edging was having the ability to keep the wheel turning smoothly with the left hand whilst holding the liner in the right and applying a gentle pressure to the plate trying not to vary the pressure at all or the line would be of irregular width”. The banding wheel was so vital to the process that Apprentices who could not master it were reassigned to the enamellers' department.

A further chore involved the acid etching process which was generally used for narrow border patterns. “Firstly prints were made using a tar like substance which would withstand the acid. These were then applied and when all were completed the china was passed to the male painters where someone, whoever was available… would completely cover each piece back and front with the same tar like substance. It was most important that this was completed with great care because the next step was total immersion in the acid and any white speck no matter how small would be affected by the acid and would result in rejection when it arrived in the warehouse.”

After immersion the china was cleaned of its protective coating. “This is where we juniors came in, for as there were no apprentice males it fell to females. The actual process was to wash each piece in a bath of turpentine and rub until all the tar disappeared. I don’t think rubber gloves had been invented, at least we didn’t have any provided but what we did have was home made treacle toffee provided by Mrs. Dean and French chalk to soothe our hands which became sore very quickly. It was a messy, smelly process but we gradually became used to it."

It was at least twelve months before Betty progressed sufficiently to be able to work with gold. When the day came she was “given a glass tile about 6 inches square and a new fine brush similar in size to the one I used on my first day.” From now on the “best red” which she had used to practise with would be used to identify her mark – in her case two small dots side by side placed to the left hand side of the trade mark and in the shadow of the foot rim, placing the pattern number above it where applicable. Apprentices were generally given the edges of the Posie pin trays to start with. They had to take care not to smudge the hand painted rose which appeared in the centre of each spray.

The aim was to progress as soon as possible to be able to work on a piece-work basis. By then they were “judged proficient enough to know how much gold we should use in a day and ask for one or two 'tots' accordingly when it was sent for. The amount of gold we used was counted against the amount of the work we produced, and anyone consistently using too much was asked to do a gold trial. There were many reasons why someone could be using too much gold without realising it, not just through carelessness. Applying the gold too thickly, too broad lines, too broad strokes in patterns for instance. If this was proved then the girl was usually transferred to another department. The gold trial consisted of being given an amount of Mikado to finish using just a penny-weight of gold”.

Betty recalls the challenge of working on replacement pieces and on the coronation ware produced for Edward VIII and George VI.

A cigarette box that on the reverse has Betty's characteristic two dot mark.

With the outbreak of War, as Betty had an Apprenticeship, she was initially allowed to remain at Royal Crown Derby until she had completed her two years as an improver. She was then directed into war work, working “in the L.M.S. railway aircraft wing, three wagon manufacture and repair sheds which had been turned over to making aircraft parts”.

Betty on her 21st Birthday

Early in 1945 Betty returned to Royal Crown Derby at the invitation of Phillip Robinson to start a training school for gilders. There was a staff shortage as many staff had been directed to join the forces and during the war no apprentices had been engaged. To encourage new apprentices to join the factory they were paid wages of £6.50 per week and relieved of some of the more tedious chores such a sweeping the stairs. The junior gilders room was relocated to the ground floor adjacent to an area where a new continuous firing electric tunnel kiln was to be installed. The new room had overhead windows and two large tables seating six girls at each. Post war improvements included new cloakrooms and a canteen providing snacks and a midday meal. Some of the old processes including acid etching had ended. Holiday entitlement at the time was one week per year in addition to Christmas and Easter.

The new electric kiln was in place in August 1946. “Production increased almost immediately because the trucks which conveyed the china through this continuous firing kiln had to be filled to capacity in order to maintain the temperature. The trucks were conveyed automatically therefore as one was filled and was placed into the kiln another one whose wares were now fired, came out the other end. This meant that it was much easier to fire a piece at each stage of the process. The hand painted roses on the Posie pattern could be fired before gilding and factory marks similarly to prevent smudging. The new kiln was not without its problems. If a stack of cranks toppled in the kiln a truck could be come stuck and the whole truck load destroyed.

At this time work started to be put out to out workers, especially gilders. Pre-war it was the practice that when any girl married they automatically left work. With no apprenticeships during the war the firm was left with just a few seniors and a workforce of predominantly junior gilders. Some of the retired employees were sought out who agreed to help and as by now the firm had its own van, the ware could be delivered and collected. Betty was responsible for settling the wages of the girls who were progressing towards piecework and therefore producing saleable ware.

Betty appears in the above photograph of the factory visit by Princess Elizabeth. She is sitting with her back to the Princess in the centre of the picture and is gilding a Vine plate. Four were allocated a place to sit at the table, specifically set up for the visit; to give everyone an opportunity, a sweepstake was held for the places. Two of the winners other than Betty. were gilders, the fourth a beginner who had only been at the factory for two weeks. Betty remembers other visits, particularly those by “Gert and Daisy” (Elsie and Doris Waters) and Petula Clarke.

Towards the end of 1949 family commitments forced Betty to relinquish her teaching post and work from home. Such was her skill and experience that she was asked to gild the more demanding pieces including the tall and low peacocks which had previously been the sole responsibility of the male gilders. She also worked on the ware produced for Kuwait including the 57 inch diameter huge rice bowls which were so large that the mould makers were unable to model the usual embossed edge and it therefore had to be drawn out by hand before it could be gilt.

Toward the end of 1959 Betty was able to return to work at the factory and started a new training school at the beginning of January 1960. This was located in a small room formerly used by the engravers, and six girls started all having left school at Christmas. With the addition of further school leavers she soon found that she was in charge of two groups, and the first progressed so rapidly that it was entrusted to gild a set of 24 dessert plates in pattern 2451 commissioned by the Governor General of Australia.

In order to provide a safer working environment and introduce modern more efficient working practices, the internal layout of the factory was radically changed to create a large open plan room with conveyor belts to transport the ware around the building. Betty's junior groups were moved into the main factory to work alongside the enamellers, senior gilders and burnishers, and she was put in charge of all junior and senior gilders, with the specific aim of improving the quality of the senior gilders' work. It is fair to say that this change in working practices gave rise to some significant resentment among the workforce, particularly the gilders. It had been the custom for work to be divided equally for fairness. The introduction of a felt roller to apply the gold edges to plates and saucers in patterns such as Mikado meant that only the cups, which needed a great deal more time and skill, appeared on the conveyor. As the gilders were paid on a piece-work basis, this had an adverse effect on wages, at least initially. Betty also found that she had to adapt her management style to cope with a situation where two decorating departments with different supervisors were now working alongside each other. It is a credit to Betty and her colleagues that notwithstanding these issues the quality of the work improved. Betty and her senior colleagues devised procedures to check and adjust or revise the ware before it was fired.

Betty's career continued long after the period covered by this website. With the introduction of silk screening in the early 1960's the transfer printing process became obsolete. Betty was tasked with painting the Imari designs onto sheets of permatrace which could then be used to make the silk screen transfers. She realised that this would inevitably reduce the number of gilders required to do the finishing off of such work but "there was little I could do about it."

In 1972 she was asked to work in the factory Museum alongside John Twitchett, as assistant Curator, with an early task of listing and describing the patterns and shapes, research which was included in her book jointly written with John Twitchett first published in 1976. Her duties included holding Open Days and escorting Museum visitors. The same year she travelled to Chicago to demonstrate her gilding skills as the firm's representative at "British fortnight" an exhibition of all things British. In 1977 she completed a five week tour of Canada and America.

Betty retired in 1984 after working for fifty years for the business.

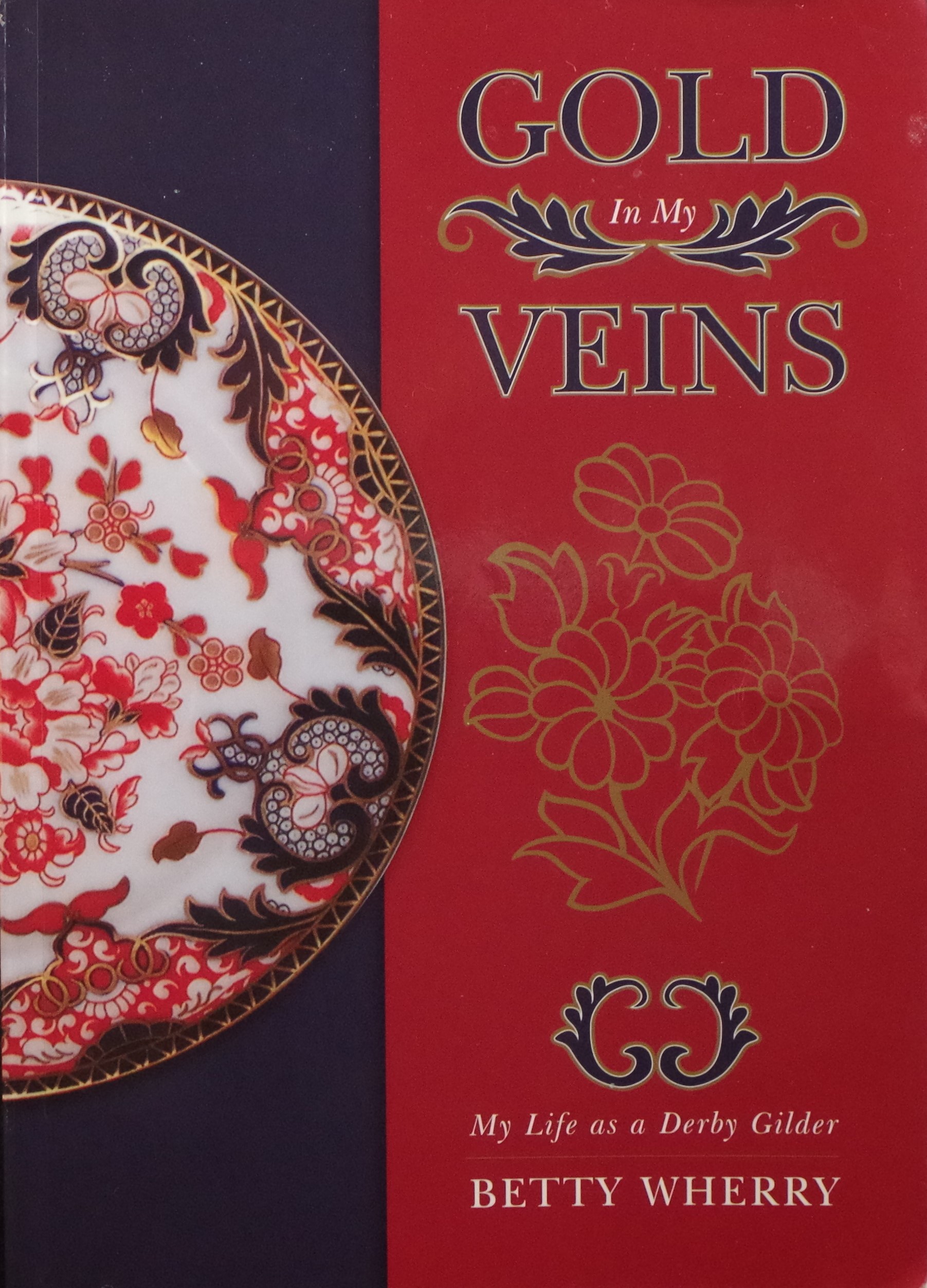

In 2008 Betty published an account of her time at Royal Crown Derby entitled "Gold in my Veins - my life as a Derby gilder." It is an invaluable resource not only for collectors, but also for social historians interested in the experiences of women in the workplace from 1934.

Published by Brewin Books Ltd, 56 Alcester Road, Studley, Warwickshire B80 7LG

ISBN: 98-1-85858-421-8

This blog has been prepared following an interview with Betty in March of this year and by reference to her autobiographical account

John and Val Robinson - November 2017